As his paintings go on show at Hauser & Wirth in London, the film-maker, writer and artist tells us about his latest genre-bending output and his biggest influences

Fifteen years ago, the American film-maker, writer and artist Harmony Korine strongly felt a convergence of the creative, technical and spiritual worlds. “It felt like a kind of singularity, where a limitless art form was emerging where everything was blending,” he says. “It made me question the meaning of art, the meaning of life. What is reality and what is fantasy? Are we in a state of post-meaning? And at that point does life become fun because it’s all just a game?”

Born in Bolinas, California in 1973 to Jewish parents, Korine’s faith has always been more mystical than religious (he talks a lot about “following the light”). “There are things that I’m drawn to that are not easy to articulate, they have more to do with a feeling and an energy, which is why I live on the ocean,” he says. Around 12 years ago, Korine and his family left Nashville for Miami; when we speak over Zoom, Korine is smoking an enormous cigar overlooking the water.

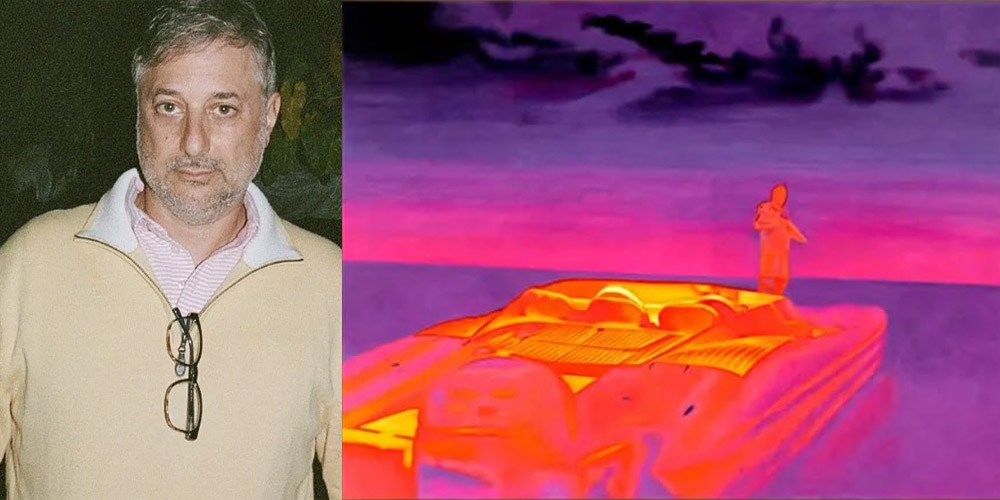

His latest genre-bending output is a film (in the loosest sense of the term) titled Aggro Dr1ft and a series of paintings derived from the film, which are currently on show at Hauser & Wirth in London (until 27 July). Aggro Dr1ft was shot using high resolution infrared cameras developed by NASA (scenes were also simultaneously shot with other types of cameras, though the infrared imagery appears most dominant). “They’re really sensitive to heat and light and form so it’s almost like [you’re shooting] colourful souls,” Korine says. “They go very quickly from abstraction to figuration and then back again, almost like carvings blocks of colour.”

Starring Jordi Mollà and Travis Scott and described in promotional material as an “adrenaline-fueled trip through Miami’s underbelly”, the film’s aesthetic also draws heavily on computer games such as Grand Theft Auto and Call of Duty. “It feels very gamified,” as Korine puts it. Last year, he set up EDGLRD (pronounced edgelord, a term for someone who shares extremist or nihilistic views, particularly on the internet), a design collective-cum-creative factory based in Miami that includes video game developers, graphic designers, as well as AI and VFX designers. “It’s a universe of people in there working on designs for everything from houses and filters to films, Twitch streams, crank shows and skateboards,” Korine says.

The film-maker and artist says he barely leaves his art studio, which is right next door to the Edglrd headquarters. “It’s very solitary by comparison. There’s something I always love about painting because it is just what it is.” Korine usually has two or three bodies of work on the go, but the Hauser & Wirth pictures are the first set of paintings he has created that have been sourced directly from his film imagery. Some of the paintings were first shown at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles at the end of last year in Korine’s debut exhibition for the gallery.

The idea behind the paintings, Korine reveals, was to try and replicate the infrared imagery in two dimensions—the resulting canvases almost have a neon, glowing quality. “I wanted to develop the colours, so we pushed the paints as far as we could until they started to corrode,” he says.

Parallels have been drawn between Korine’s work and that of Richard Prince or even Peter Doig. He has cited Oyvind Fahlstrom, Martin Kippenberger and William Eggleston as art historical influences, but looks equally to comedians and actors such as Milton Berle, Groucho Marx and Chevy Chase. Perhaps more than anything else, Korine has been influenced by the designer, architect and film-maker Charles Eames’s idea of a “unified aesthetics”. As Korine says: “There are no borders with art, artists can really play around with all forms. All mediums converge, high and low and everything in between. The paintings, the writings, the films, they are all a kind of singular vision.”

Some aspects of Korine’s multi-dimensional oeuvre have been better received than others. Context can be everything. Aggro Dr1ft premiered at the Venice Film Festival last year where half of the audience walked out midway, while the other half gave it a ten-minute standing ovation at the end. Early on, Korine garnered a cult following for films such as Larry Clark’s Kids (1995), which he wrote the screenplay for when he was just 19, and Gummo (1997), his directorial debut consisting of a collage of unrelated and disturbing vignettes that take place in a tornado-ravaged town called Xenia in the state of Ohio.

In 2021, a documentary about Kids was released in which some of the actors spoke out about feeling exploited during filming. Many of them were skaters whose own turbulent lives were reflected in the film and only reportedly received a thousand dollars for their work on set. Korine, who was also part of New York’s skate culture at that time, says he “never really felt” Kids was exploitative. “It always felt like everyone was trying to tell a story,” he says. “None of us had ever made a film before. The whole movie was a million dollars. It was a miracle that the film even existed.”

Writing was Korine’s first passion, though he says he never thought of himself as a writer. Not formally trained—he stuck out one semester studying creative writing at New York University—Korine says he “just tried to figure it out” on his own. “I was more into skateboarding. And then I decided, around 16 or 17, that I wanted to make movies,” he says. “My dad gave me some good advice because he never wanted me to have to depend on other people, so he said I should learn to write my own scripts, tell my own stories. I hated the idea of filming someone else’s idea; I always had a short attention span.”

Duration is something Korine has been pondering lately. “What if a movie could be ten seconds?” he questions. “If life is a movie, every blink could be an edit.” Aggro Dr1ft runs at an almost feature-length one hour and 20 minutes, though there is no real narrative and little continuity. “I’m not even sure it’s a film—I wasn’t convinced that it was something that I wanted to put in conventional theatres,” he says.

The artist says he has been more excited by the live events that have accompanied the film. It was shown in a strip club in Los Angeles called Crazy Girls in January and at EartH in Hackney earlier this month—where Korine suggested people “take molly and have fun” in a viewing more akin to a rave than a cinema screening. Korine himself DJ-ed alongside the Venezuelan musician Arca and the British electronic producer Evian Christ.

Korine’s next film, which he has almost finished, promises to be even less conventional. “I can’t talk about it too much but, tentatively, it’s called Baby Invasion and it kind of functions like a first-person shooter. It’s very frenetic,” Korine says. “I’ve definitely never made anything like it before.”

If Aggro Dr1ft is anything to go by, the art world has probably never seen anything like it before either.

Photo title:

Harmony Korine, STILTS ZOON X2 (2023)

Photo: Keith Lubow. © Harmony Korine Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth